Why

are distorted faces so frightening? Freud classified certain objects as

'unheimlich,' a difficult-to-translate word akin to 'uncanny': strange,

weird, unfamiliar. Waxwork dummies, dolls, mannequins can frighten us

because we aren't immediately sure what we're looking at, whether it's

human or not, and that causes anxiety. A surprisingly large part of the

human brain is used to process faces. Identifying friend from foe at a

distance was an essential survival skill on the savannah, and a damaged

face is thought to somehow rattle this system.

The psychologist Irvin Rock demonstrated

this in his landmark 1974 paper 'The perception of disoriented figures.'

Rock showed that even photos of familiar faces -- famous people like

Franklin D Roosevelt, for instance -- will look unsettling when flipped

upside down. Just as, if you tip a square enough it stops being a square

and starts becoming a diamond, so rotating a face makes it seem less

like a face. The mind can't make immediate sense of the inverted

features, and reacts with alarm. A bigger change, such as taking away

the nose, transforms the face severely enough that it teeters on no

longer seeming a human face at all, but something else.

That

isn't a theoretical example picked out of the air. On another visit to

the Craniofacial Center, I enter Seelaus's examination room to be

introduced to a patient. He turns in the chair, and is missing the

middle part of his face. There are four magnetic posts where his nose

will go, and below it, a void revealing smooth yellow plastic. My eyes

lock on his eyes, I shake his hand and say some words.

A

half-hour later, standing on the elevated train platform, I still feel

... what? 'Harrowed' is the word that eventually comes to mind. Why?

There was no surprise. I'm no longer a child but an adult, a newspaper

reporter who has spent hours watching autopsies, operations, dissections

in gross pathology labs. I was expecting this; it's what I came here

for. What about his face was so unsettling?

Maybe

seeing injured faces compels an observer to confront the random cruelty

of life in a raw form. Maybe it's like peeling back the skin and seeing

the skull underneath. Like glimpsing death. Maybe it touches some

nameless atavistic horror. That's as far as I get before the train

arrives and I get on.

School days

Randall H James was born in Ohio in 1956. His first surgeries were done over the next couple of years at Cincinnati Children's Hospital by Dr Jacob Longacre, a pioneer in modern plastic surgery.

"He

was like a second father to me because I saw him so much," says James,

who didn't celebrate a Christmas at home between the ages of 3 and 13.

School holidays were for operations. Summers too.

When

little Randy began school, his teachers in the city of Hamilton made a

common mistake, the sort of automatic connection between inner person

and outer appearance that has been the default assumption since history

began.

"The teachers assumed I must be

stupid," says James, who was put in a class with children who had

learning disabilities -- until teachers realized that he was actually

very bright, only shy, and missing an ear, which made it harder for him

to hear. He was allowed to sit in the front of the room, where he could

hear the teacher, and his grades soared.

Doctors

constructed him a large, puffy, vaguely earish appendage. It looked

like a coil of dough, like a boxer's cauliflower ear. It wasn't much

help.

As a student at the University of

Kentucky, James applied to be a residence hall adviser, someone who

assists other students in navigating dorm life. The supervisor who

rejected him candidly told him that his odd-looking ear could put others

off.

"'You might make the students

nervous,'" James recalls him saying, then paused, the pain still obvious

after 40 years. "These were my classmates."

History concealed

We

are a society where people thrive or fail -- in part, in large part --

because of appearance. The arrangement of your features goes far in

deciding who you are attractive to, what jobs you get. Study after study

shows that people associate good looks with good qualities, and impugn

those who aren't attractive. Even babies do this, favoring large eyes,

full lips, smooth skin. Billions of dollars are spent on plastic surgery

by people who are in no way disfigured, just for that little extra

boost they feel it gives to them, gilding the lilies of their

attractiveness.

How do people with

unusual appearances fit into such a world? For most of recorded history,

children born with disfigurements were wonders, portents or

punishments. If they were allowed to live. "A couple hundred years ago,

people born with craniofacial conditions, they were just putting them in

a bucket of water," said Dr David Reisberg, an oral plastic surgeon at

the Craniofacial Center.

But even then,

astute observers saw beyond externalities. Michel de Montaigne in 1595

encountered a child conjoined to the half-torso, arms and legs of an

undeveloped twin (what we would now call a parasitic twin), displayed by

its father for money. Montaigne noted: "Those that we call monsters are

not so to God, who sees in the immensity of His work the infinite forms

that He has comprehended therein."

Adults

were another matter. Those who came upon their distinctive faces later

in life were seen as having been dealt their due, either through heroism

in battle -- dueling scars were so fashionable in 19th-century Germany

that young men would intentionally wound themselves -- or through the

outward manifestation of inner sin. Plastic surgery began its first,

faltering steps as a separate field of medicine after Columbus brought

back syphilis from the New World in the 1490s, the injurious effects of

which include destruction of the nasal cartilage. Soon silversmiths were

fashioning metallic noses, and surgeons were cutting triangular flaps

from patients' foreheads and twisting them to form rudimentary new

noses. Sometimes that even worked.

The twin impulses, to conceal and to correct, have been competing ever since.

Perhaps

the most surprising thing about the history of plastic surgery is how

old it is. The use of the term 'plastic' to describe a type of medical

operation was popularized in German surgical texts in the 1820s, long

predating its 20th-century use for the synthetic material.

British

doctors in 19th-century India advanced plastic surgery while trying to

repair the noses and lips local warlords cut off as a mark of disgrace.

But plastic surgery truly entered the modern age after World War I.

Trench

warfare created facial injuries with a grim efficiency. The trench

protected your body and the helmet protected your head, saving your life

but not your face. Historians estimate that 20,000 British soldiers

returned home with mutilated faces after the War. Society wrestled with

contradictory impulses: to seek them out and to shun them. The scarred

faces of soldiers were highlighted in books and exhibitions, both to

show off what was possible through modern medical technology and to act

as a cautionary tale of the horrors of war.

Yet in Britain there were also schemes to segregate those with facial injuries in their own villages, to keep them out of sight.

In

the 1920s, almost every café in Paris had its pensioned veterans.

"Croix de Guerre ribbons in their lapels and others also had the yellow

and green of the Médaille Militaire," Ernest Hemingway notes in A

Movable Feast. "I watched... the quality of their artificial eyes and

the degree of skill with which their faces had been reconstructed. There

was always an almost iridescent shiny cast about the considerably

reconstructed face, rather like that of a well packed ski run, and we

respected these clients."

Sir Harold

Gillies set up his famous hospital during World War I in Sidcup, a small

English town, which soon found itself populated by servicemen having

their faces rebuilt. Certain park benches were painted blue, as a code

to the townspeople to brace themselves for the patients who might be

sitting upon them, and thus not be startled as they approached.

This

"startle" reaction is a cause of much distress, both for people with

disfigurements and for those they encounter, who must compress the

lengthy adjustment period that recovering patients themselves go through

into a moment, and tend not to do it well.

Until

not so long ago, those reluctant to see people whose appearances stray

beyond the range of the usual actually had the law on their side. Many

cities in the United States had 'ugly laws' designed primarily to reduce

public begging. Chicago's law read:

Any

person who is diseased, maimed, mutilated or in any way deformed, so as

to be an unsightly or disgusting object, or an improper person to be

allowed in or on the streets, highways, thoroughfares or public places

in this city, shall not therein or thereon expose himself or herself to

public view ...

The law was not repealed until 1974.

Survivors

"So

Randy, can I take your bar off?" says Rosie Seelaus. James has a white

gold C-shaped armature permanently fixed to the side of his head,

anchored to his skull with gold screws. The prosthetic ear snaps onto

the bar. "I'll take your bar off so I can make the substructure. At

lunch we can look at images we have."

It

is Monday. James is in Chicago for the entire week, having his new ear

created. Seelaus removes the screws and lifts the metal structure from

the side of his head, the first time it has been taken off in seven

years, since he decided to replace the crude ear surgeons had created

for him with a prosthetic.

"If this

were fitting well we could use the same mold and just replace the

silicone," she says of James, who has lost 24 pounds, which threw off

the fit of his ear. "But since it's not fitting well, we're going to be

starting from scratch and redesigning ... Tomorrow will be mostly

sculpting his ear."

This involves a

range of high-tech gear. A CT scan is taken of his left ear. A computer

then creates a mirror image of that scan, which a milling machine uses

to carve a right ear out of a block of dense blue wax. Seelaus takes

this prototype and makes a second, skin-toned ear from softer dental

wax, which she puts on James to adjust its form and fit. A colorimeter

and a spectrophotometer are used to gauge exact color values.

"Color

is essential to having a successful prosthesis outcome," says Seelaus,

who spends hours matching shades, then fitting James's ear to his head

-- even the most perfect, natural looking ear will fail if there's a gap

between it and the wearer's head. When she's done, the ear is then

pressed into dental stone to create a mold that she fills with silicone

to make the final ear. She mixes liquid pigments into splashes of clear

silicone, colors she dabs into clear plastic, which she holds against

James's head, trying to match his skin tone. Seelaus doesn't pour the

colored silicone into the mold; she paints it in, layer by layer. To

imitate tiny veins, she uses strands of red and purple yarn.

Matching

the appearance of each individual is crucial. She has, for instance,

created ears that were partially burned, to match scarring on a burned

face.

"This is a full-life journey for

these patients," says Seelaus, who has done this work for 16 years. "I'm

still learning from patients about what their life experience is and

how it changes. Being born with a facial difference becomes a life

journey that has a lot to do with acceptance. I've learned with patients

who are burn survivors -- not victims, survivors -- initially their

relationship with the prosthesis changes, too, throughout their lives

... What I try to tell them is, they've been through a lot already, it

will also take adapting to the new way they look."

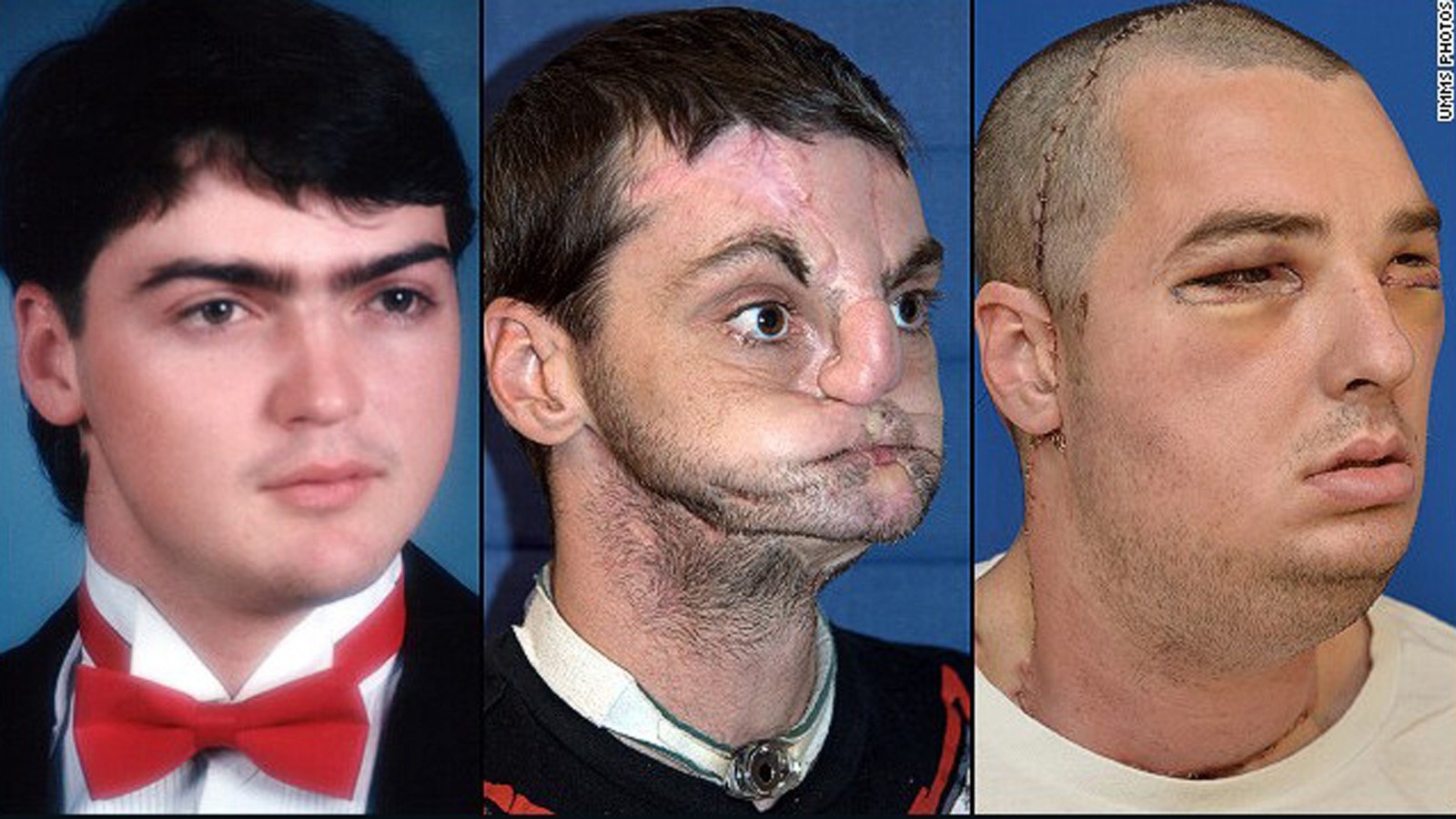

How

people fare on this journey generally depends on what they start with.

"It's about your self-perception before the incident," Seelaus says.

And

self-perception really matters. A Dutch study in 2012 looked at how

well people with facial disfigurements functioned socially, finding that

their satisfaction with their appearance was more important than the

objective severity of the disfigurement.

Not

that living with a face that is far beyond the mainstream is ever easy,

or purely a matter of confidence. It isn't. It's a struggle, Seelaus

says, requiring courage and endurance.

"People

who sit in this chair are survivors," she says. "They don't come to me

in this chair without having survived something, and often it's a lot.

It takes resilience to get through the treatment. And what they've been

through living day-to-day in society takes a resilience we may never

understand if we don't go through that. Burn survivors have a resilience

that is phenomenal. The reality is, it can happen to anyone. And so

maybe that will bring about compassion."

"A Face for Me"

Is

greater public compassion on the way? Stares and thoughtless comments

are a daily part of life for people with disfigurements. But there are

many groups that have long suffered abuse at the hands of society but

are now better accepted. Is there any hint that those with damaged faces

are traveling the same path that, say, people with Down's syndrome are

taking towards being more fully welcomed and integrated by society?

"People

would really have to change a lot to make facial deformity the new

normal," says Kim Teems, Communications and Program Director at FACES,

the National Craniofacial Association. "It's a very hard thing to go

through, not only being looked at strangely, but all the pain of

surgeries."

Based in Tennessee, FACES started in 1969 as the Debbie Fox Foundation.

Fox has an important if forgotten role in the glacial social progress

of people with disfigurements. She was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee,

on 31 December 1955, with a massive cleft from her upper lip to her

forehead, her eyes pushed to the sides of her head: basically a hole

where her face should be.

"Her parents

resigned themselves to raising their youngest daughter as a hidden

child -- secluded from outside eyes," a newspaper account noted.

Fox

said she had never seen her own face until she was eight years old and

found a hand mirror. She screamed in terror. "So that was what I looked

like," she wrote in her 1978 autobiography, A Face for Me. "That was why

I couldn't play with the other children, go to school, go to church,

run into the store to buy candy or ice cream. All these things had been

forbidden to me."

By third grade she

attended school via telephone hookup, standing to recite the pledge of

allegiance with classmates she'd never met. When, at age 13, she was

driven to Atlanta for reconstructive surgery, it was the first time she

had left her hometown, the first time she had eaten in a restaurant --

in the back, at off hours, but in a real restaurant.

It

was also when "the girl without a face" caught wider public attention.

The magazine Good Housekeeping ran a story about Fox in 1970 that showed

her only from the back, a squeamishness that the media still struggle

to overcome. Seeing people different from oneself can be a helpful step

towards accepting them, but for people with disfigurements, public

visibility has been slow in coming. Some progress has been made, though.

Esquire magazine put a soldier missing both legs and an arm on its

cover in 2007, and in 2010 featured inside a straight-on photograph of

the film critic Roger Ebert with most of his lower jaw removed because

of salivary gland cancer.

Educating the public

Randy

James is not optimistic. As someone who not only wears an artificial ear

and has sprays of scars under his jaw, but also is a doctor working

with veterans whose faces have been damaged by war or illness, he

doesn't see much improvement in how society views people with facial

disfigurements.

"In some ways it's

worse," James says. "With the rise of social media, you can be an

anonymous bully. If you're not attractive, in many ways you're not going

to be successful in society.

"I

was working at St Mary's Medical Center in Huntington, West Virginia. I

had just gotten my [prosthetic] ear right before I started there. Had I

not had my new ear, which really changes my appearance, would they have

made me one of their poster boys promoting their hospital? I can pretty

much guarantee they wouldn't have done that if I had my old ear."

Some

disagree. Just as World War I injected people with disfigurements into

the general population, so have a dozen years of warfare in Afghanistan

and Iraq, and this new generation of veterans is having an impact on how

those with a wide variety of severe injuries are viewed.

"With

our current conflicts, we're seeing injures far more catastrophic than

we used to see," says Captain Craig J Salt, a plastic surgeon at the U.S. Naval Medical Center in San Diego, California.

"Massive

tissue destruction, horrific burns ... The combination of the level of

destruction with amazing lifesaving capability of the front lines gives

you a patient population who would not have survived in the Vietnam era

... We have people entering rehabilitation horrifically disfigured in

significant numbers."

Salt, who led the

Navy's effort to begin treating facially wounded veterans with the same

team approach used for treating cleft palates, says, "My impression is

society is more accepting and more aware of the magnitude of injuries

our soldiers and sailors, marines and airmen are coming back with.

They're more accustomed to seeing disfigured patients because of media

awareness, with social media ... people might be a little less shocked

to see a disfigured patient."

Soldiers in Britain echo Salt's sentiment.

"Since I was injured five years ago, the profile of disability and

injured service personnel has grown massively," says Joe Townsend, a

Royal Marine who lost his legs to a bomb in Afghanistan.

"Unfortunately,

a lot of that's down to the growing number of guys and girls coming

back from Afghanistan with life-changing injuries, but the progress made

by charities and the awareness on the television has really helped to

educate the general public ... Before, I'd walk down the street and I'd

notice people looking at me, but it's pretty much an everyday occurrence

to see someone injured now."

Townsend

says this in Wounded: The Legacy of War, a coffee table book of

beautiful, fashion-style photographs of wounded British soldiers, taken

by the rock singer Bryan Adams.

Facial equality

It

is tempting to point books such as Wounded, and other popular culture

treatments of disfigurement, and aggregate them into a sign of progress.

Wonder by R J Palacio is a young-adult book that tells the story of

August, a ten-year-old with severe facial differences trying to adjust

to school life for the first time. "If I found a magic lamp and I could

have one wish, I would wish that I had a normal face that no one ever

noticed at all," August confides, on the first page.

And

these works do have an impact. Wonder was on the New York Times

bestseller list for 97 weeks. Even a decade ago, a child such as Mary

Cate Lynch, three, might seldom have gone out in public. She was born

with Apert syndrome, an extremely rare genetic condition that affects

her head, face, feet and hands. But today, Mary Cate has her own cheery

website, introducing her with photos and video. Her mother, Kerry Lynch,

has taken her to 80 Chicago-area schools to present a program, often

tied to the class reading Wonder, that explains Apert syndrome.

"Every

parent does what they think best," says Lynch, a nurse. "I thought the

best thing I could do is to educate others so they wouldn't be afraid of

it. Fear comes from the unknown. I just thought

if I could tell others about it, show them that, yeah, she's a little

bit different, but she's more similar. If I could explain what these

differences are, be very candid about it, that's what I could do to help

her in her life."

Society takes a long

time to accept people who look in any way different. Many Americans

thought Irish immigrants, as a class, were ugly when they migrated in

numbers to the USA in the 1850s, mocking them for their features,

holding them up as signs of congenital inferiority. A few decades later,

they marveled at how much these same Irish immigrants had somehow

changed -- "even those born and brought up in Ireland often show a

decided improvement in their physiognomy after having been here a few

years," Samuel R Wells wrote in the 1870s, making the common error of

confusing a shift in one's own perception with a change in the object

being perceived. Irish faces didn't actually change; the American

public's antipathy did, slowly and without their even being aware of it.

Awareness

of the challenges facing people with facial differences has not yet

grown enough to smooth the path of any given adult walking into a

restaurant or any given child showing up on a playground. But the seeds

of improvement are definitely being planted. In Britain, the group Changing Faces put

posters of disfigured people on the London Underground. Its founder,

James Partridge, read the noon TV news in London for a week in 2009 to

show that, while delivering information may be monopolized by the

beautiful, it doesn't have to be.

"Are

things changing?" says Partridge. "I think it's very much about where

you look ... In 2008 we launched our campaign for face equality. We

started public awareness, putting posters up, saying, 'Have a look at

these characters, they're okay.'

"We

definitely had an impact ... [though] outside of the confines of

Britain, much less. Though in Taiwan there is a Facial Equality Day in

May. In South Africa, the message of facial equality is very easy for

them to pick up. I think it's such a simple concept, the prejudices we

need to attack."

Face to face

In

1998, the Italian fashion company Benetton ran a series of ads

featuring people with disabilities. The ads awakened the guilt I still

felt about Cynthia Cowles. I realized we had some unfinished business. I

tracked down her phone number and called her, writing about our

conversation in a Chicago Sun-Times column published at the time.

Talking

to Cynthia was awkward for the first five seconds. Then we were old

classmates, laughing and sharing stories. She said she had seen me

interviewed on TV.

"You still play with your shoelace when you're nervous," she said.

I was nervous now. I told her I was sorry for being mean to her in grade school.

"If

you were mean to me, there were so many other people who were so much

worse," she said. "I recall you as being one of the kinder people. You

were the one in eighth grade who came to visit me in the hospital -- you

told me your mother made you come, but you stayed a half-hour, very

uncomfortably -- and brought a box of stationery."

I

have no memory of that, though spilling the beans about my mother's

command was exactly the sort of dopey, over-honest thing I would say,

then and now. She recalled feeling sorry for me.

"You

got teased for being fat, and got teased because you couldn't skip,"

she said, recounting how the gym teacher tried to drill me into

skipping.

After we caught up -- we both

had got married -- I asked her something I had always wondered about.

What exactly was the cause of her disfigurement?

"I

was basically born without bone in my nose, and the front of my

forehead was not closed," she said. "I'm hydrocephalic, which means my

head is bigger than it should be, which put pressure on my brain."

She had more than 60 operations. "Now I'm done," she said.

We

laughed a lot, particularly when she told a story about dealing with

her tormentors. "My mother always thought if you ignored it, it would go

away," she said. But that only went so far, and one day she turned

around and socked a kid who was teasing her, then was terrified because

she realized the assistant principal had been standing right there and

saw her.

"But he just gave me the thumbs-up sign, and said, 'If you didn't, I was going to.'"

A matter of perception

On

Friday, Seelaus heats James's new ear in an Imperial V Laboratory Oven,

then, wearing light green oven mitts, removes the cylindrical mold.

After it has cooled, she pries the sections of the mold apart. "Look at

that," she says, brushing away excess silicone, then almost sings, "I

think that looks pretty goooood."

She

lifts out a startlingly human-looking ear. With a few trims and a touch

of color here and there, she attaches it to James's head. From two feet

away you can't tell it isn't a natural human ear. James is delighted.

"It looks a lot better, huh hon?" he says to his wife, who has come to

see the final result. She later pronounces the new ear "sexy".

Seelaus

gives him some practical care tips. Keep away from solvents, small

children and pets -- animals like to chew silicone. The ear will sink.

"If you go swimming, if you're in the ocean, wear your old ear," she

says. "Don't put it on top of a radiator or toaster oven."

I

estimate the ear costs $10,000 -- its fabrication took up most of

Seelaus's working week -- and she does not contradict me. I also observe

that Seelaus must be one of the few artists who hopes that her work

goes entirely unnoticed by the public, and she doesn't contradict me

about that, either.

Happy though he is

with his improved appendage, when I ask James if I could take a picture

of him wearing his new ear, he refuses. He says he is worried, not

about the photo's appearance on Mosaic, but that it might later be

lifted and included in some online "hall of monsters". I ask several

times in several ways, reassuring him that in my view this is highly

unlikely. His answer is always the same: No. A reminder that looks are

always relative, always only part of the story, and that our reaction to

them fills in the rest.

There is no such reluctance with Seelaus's next patient, Victor Chukwueke, a Nigerian-born medical student with neurofibromatosis,

a disease of rapidly growing tumours that crushed his jaw, distorted

his face, and left his right eye an empty hollow. He is here to get a

new false eye and surrounding socket, to help put his future patients at

ease. Even without a prosthetic, however, with a scarred void where his

right eye once was, he smiles and poses as I click away.

Seeing

people with disfigurements is important, because once a person, or a

society, becomes familiar with them, apprehension fades. Just a couple

of weeks before, I had needed to steel myself, sitting in my car in the

parking lot of the Loyola University Medical Center, on my way to

interview burn survivors, actually saying out loud, "If they can live

it, I can see it," to gather my courage.

But

by the time I meet Chukwueke, that trepidation is gone. I had asked

Seelaus to send me a photo of him, so I could prepare myself ahead of

time, but she didn't, and I go in cold. Hurrying into the Craniofacial

Center, I spot a man who is obviously him, plop into the chair next to

him and introduce myself, and we immediately begin to talk. His speech

is sometimes hard for me to understand, because of his damaged jaw, so I

have to lean in very close, our noses inches apart, as we talk to each

other. It seems the most normal thing in the world.

Chukwueke puts his situation neatly into perspective.

"We

all have an issue," he says. "We all go through things in life, go

through difficulties. You don't have to let your challenges bring you

down or let you be sad and depressed. It's a matter of perception. How

you see it."

Source: CNN, 23rd June 2015