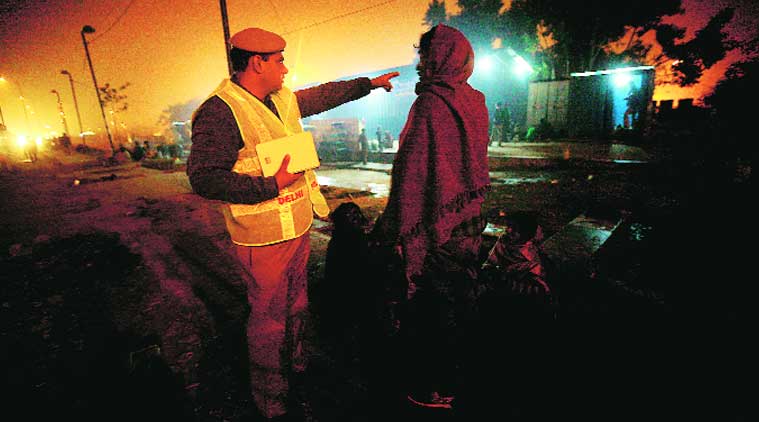

On winter nights, Lalit Kumar has to make sure the homeless move into night shelters. But many of them would rather spend their nights in the open.

On a cold winter night, the scene outside Hazrat Nizamuddin railway station at Sarai Kale Khan in southeast Delhi is one of chaos. Harried passengers lug their baggage around and sip endless cups of chai as they wait for trains running hopelessly off schedule. Those who’ve just got off trains haggle with auto drivers, and those who’ve just arrived at the station bargain with porters. Hawkers selling woollens stay busy as people scramble for extra layers as the night gets chillier and foggier.

All this while, sub-inspector Lalit Kumar and nine other men in khaki walk around, keeping a general ‘nazar’ on everyone. They are on duty here every night, but this winter, they have one more task on hand — to ensure no homeless person sleeps on the pavements, but in the six night shelters, or rain baseras, near the Sarai Kale Khan crossing. In November, the Supreme Court directed governments in Delhi, UP, Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana and Bihar to set up enough night shelters to house the homeless during winters.

Kumar, 45, standing tall at six feet, is in charge of the Sarai Kale Khan chowki near the railway station. After spending the day in courts and following up on police complaints, he begins his night patrols at 9 pm. With a walkie-talkie in hand, he approaches a family of five squatting on the pavement. “Chaliye, aap rain basera mein jaiye. The night shelters have blankets and mats. Where are you going to take your small children in this cold,” he tells them assertively. The family, though, is having its meal, and is no hurry to heed Kumar’s order.

The Capital’s 250 night shelters, built by the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board, are porta-cabins that can accommodate up to 50-60 people at a time. With mats spread on the floor, the shelters are stocked with blankets, and some even have televisions. And yet, getting people to sleep inside these shelters, says Kumar, is “not easy”. According to him, there are two “categories” of homeless. One, labourers who’ve just got off the trains at Nizamuddin in search of work and who have nowhere to go. They are easy to persuade and are usually happy to get into the shelters. The others are, what he calls, “professionals”. “These have been living under the flyover and on the streets for years, and refuse to go into the shelters,” he says. They are “hardened and obstinate”, know the city well and have learnt to survive its harsh conditions. “They can survive on meals bought for Rs 5,” he says, pointing to families cooking meals in the open.

Kumar’s teammate, a constable, waves his lathi at a group of people and shouts, “Come on. Get up and get inside. Right now. All of you. Do you want to die of cold and kill your children too?”

“Why should we go? All our saamaan is here. You won’t let us take all this inside the rain basera,” shouts back Komal, a scrap-dealer. As she quickly fills a gunny sack with the motley wares she has collected, she snaps at her husband Shambu: “And you stop dropping my utensils”. As she continues grumbling, Kumar reasons with Shambu: “Please cooperate. You cannot stay here. Take your family inside.”

Shambu nods, crosses the road with his wife and children, and steps inside the rain basera.

An hour into such heated negotiations, many of the homeless, including children barely two feet tall, begin dragging out sacks full of clothes and utensils from under the flyover. Grumbling and squabbling, they get inside the the night shelters.

But some, like 35-year-old Asma, a daily-wage construction labourer, refuse to budge. “We have been living here for the last 20 years. When we sleep here in the searing summer, no one bothers. So why do you suddenly turn up when it gets cold?” she says. Asma doesn’t want to spend the night in the shelters as she has two grown-up daughters. “There are drunk and dirty men in the baseras. The police simply push us into these shelters and then they are nowhere to be seen,” she adds.

It’s almost midnight and Kumar heads back to his chowki for a quick bite before setting out on another round of patrol, this time to keep an eye on thieves and pickpockets. Over roti and spinach curry, Kumar explains his winter job: “By court orders, we cannot allow even one death due to the cold. Otherwise, it would mean our system has failed.”

About 100 homeless people have died in the city this winter so far, though Kumar denies there have been any deaths in his area.

He pulls out his phone and shows us photographs of homeless children scurrying for blankets and woollens handed out by the police. “We develop a bond, a familiarity over time. The street dwellers know my name and I know theirs. We may squabble, but there is mutual understanding too,” he claims.

Sub-divisional magistrate (Defence Colony) Hemant Kumar, heading home after finishing his rounds, says it’s unfair to blame the administration for the deaths. “These people are stubborn. They’d rather sleep here, out in the cold, because the rich drive down here and donate blankets and woollens. They think they are doing a good deed but these people sell the blankets off to dealers for Rs 200-300 each,” he says.

Bappa, a homeless beggar, admits he sells the blankets and woollen clothes “the bade sahibs give us”. “We need the money. But that is not the only reason why we choose to sleep outside. The rain baseras are cramped. Drunk men get into brawls and many fight for space. They push me and my wife around, even though both of us are physically challenged. Gareebon ki koi izzat nahi hoti hai.”

After about two hours of patrolling the streets, Kumar returns to his chowki. It’s 2 am, and time for a nap. Rubbing his palms together to beat the chill, he checks with his team to see “if everything is normal” before heading to a partitioned chamber in the chowki that has a cot and a TV. “I will sleep for two hours, step out for another round of patrolling and then try and catch another two hours of sleep. We squeeze in enough rest to keep us going through the day,” he says.

Source: The Indian Express, 11th Jan 2015

No comments:

Post a Comment